Evaluation and Management of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease State of the Art Review

Singular Clinical Presentation of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux: A v-Year Case Series

i

Department of Human Beefcake and Experimental Oncology, Mons School of Medicine, UMONS Enquiry Institute for Health Sciences and Technology, University of Mons (UMons), B7000 Mons, Belgium

two

Department of Otolaryngology-Caput & Neck Surgery, Foch Hospital, Schoolhouse of Medicine, UFR Simone Veil, Université Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines (Paris Saclay University), 92150 Paris, France

3

Section of Otolaryngology-Caput & Cervix Surgery, Ambroise Paré Hospital, APHP, Paris Saclay University, 92150 Paris, France

four

Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, CHU Saint-Pierre, Faculty of Medicine, Academy Libre de Bruxelles, B1000 Brussels, Belgium

v

Elsan Polyclinic of Poitiers, 86000 Poitiers, France

vi

Department of Otolaryngology, Hospital Complex of Santiago de Compostela, 15700 Santiago de Compostela, Spain

7

Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, EpiCURA Infirmary, B7000 Mons, Belgium

8

Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, AHEPA University Infirmary, Thessaloniki Medical School, 54621 Thessaloniki, Hellenic republic

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

†

Sven Saussez and Petros D. Karkos are equally contributed to the newspaper and have to be co-senior authors.

Bookish Editor: Emmanuel Andrès

Received: 13 April 2021 / Revised: 21 May 2021 / Accepted: 28 May 2021 / Published: 31 May 2021

Abstract

Background: Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is a common disease in otolaryngology characterized by an inflammatory reaction of the mucosa of the upper aerodigestive tract caused past digestive refluxate enzymes. LPR has been identified as the etiological or favoring factor of laryngeal, oral, sinonasal, or otological diseases. In this case series, we reported the atypical clinical presentation of LPR in patients presenting in our dispensary with reflux. Methods: A retrospective medical chart review of 351 patients with LPR treated in the European Reflux Clinic in Brussels, Poitiers and Paris was performed. In gild to exist included, patients had to report an atypical clinical presentation of LPR, consisting of symptoms or findings that are non described in the reflux symptom score and reflux sign cess. The LPR diagnosis was confirmed with a 24 h hypopharyngeal-esophageal impedance pH study, and patients were treated with a combination of diet, proton pump inhibitors, and alginates. The singular symptoms or findings had to be resolved from pre- to posttreatment. Results: From 2017 to 2021, 21 patients with atypical LPR were treated in our eye. The clinical presentation consisted of recurrent aphthosis or burning mouth (Northward = 9), recurrent burps and abdominal disorders (Northward = two), posterior nasal obstacle (North = 2), recurrent acute suppurative otitis media (Due north = ii), severe vocal fold dysplasia (N = ii), and recurrent acute rhinopharyngitis (Northward = 1), fierce (N = one), aspirations (N = 1), or tracheobronchitis (N = 1). Abnormal upper aerodigestive tract reflux events were identified in all of these patients. Singular clinical findings resolved and did not recur after an acceptable antireflux treatment. Conclusion: LPR may nowadays with various clinical presentations, including mouth, heart, tracheobronchial, nasal, or laryngeal findings, which may all backslide with acceptable treatment. Futurity studies are needed to ameliorate specify the relationship between LPR and these singular findings through analyses identifying gastroduodenal enzymes in the inflamed tissue.

1. Introduction

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) may exist defined as an inflammatory condition of the upper aerodigestive tract with tissues related to the direct and indirect upshot of gastric or duodenal content reflux, inducing morphological changes in the upper aerodigestive tract [i]. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and LPR share some common pathophysiological mechanisms simply may differ regarding the nature and fourth dimension of occurrence of reflux events [1]. Many basic science studies have demonstrated that the mucosal lesions are mainly due to the extra- or intracellular pepsin activity into the upper aerodigestive tract mucosa [2,3]. Pepsin was found in the nasal mucosa of patients with resistant chronic rhinosinusitis and LPR [iv]. Others identified LPR equally a fundamental condition responsible of nasal symptoms in patients who do not study sinonasal infection [five]. In the same style, pepsin and LPR were identified equally important factors in the development of chronic otitis media in children and adults [6], laryngeal disorders [seven], or bronchial irritation in patients with asthma [8]. The involvement of LPR in many respiratory and digestive weather may pb to atypical clinical presentation of the disease, which may exist difficult to detect in clinical practice.

This newspaper attempts to present a instance serial of patients with atypical clinical presentations of LPR diagnosed in our reflux dispensary.

2. Methods

ii.1. Design, Information Collection, and Setting

A retrospective medical chart review of patients who were diagnosed with LPR from 2017 to 2021 at the European Reflux Clinics (Brussels, Paris, Poitiers) [nine] was performed. The LPR diagnosis was made through 24 h hypopharyngeal-esophageal multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH monitoring (HEMII-pH) respecting predefined criteria in patients who initially reported LPR-related symptoms, e.k., hoarseness, dysphagia, throat pain, throat clearing, halitosis, or globus awareness [ten].

The atypical LPR was divers as a clinical presentation with symptoms or findings that are not reported in the reflux symptom score (RSS) [11] or reflux sign assessment (RSA) [11]. RSS is a 22-particular patient-reported upshot questionnaire that reports the most prevalent otolaryngological, digestive, and respiratory symptoms associated with LPR. RSA is a finding instrument including the well-nigh prevalent signs associated with LPR. Thus, the evolution of the RSA was based on an initial observational written report analyzing the prevalence of oral, laryngeal, and pharyngeal findings associated with LPR in patients with a confirmed diagnosis (HEMII-pH). Both scores were developed after a systematic review of the virtually prevalent LPR symptoms and signs reported in the literature [12] and may be considered every bit a complete, reliable, and validated patient-reported outcome questionnaire or finding musical instrument [11].

The association between atypical findings and LPR was confirmed if the LPR diagnosis was confirmed with HEMII-pH, if the finding resolved posttreatment, and if the singular finding of the patient was non explained by some other condition. Rigorous exclusion criteria were subsequently used to select well-matched samples, to minimize bias, and to eliminate confounding factors. Patients with other comorbidities unlike from LPR or gastroesophageal reflux illness (GERD) such every bit smoking, drinking, or an agile allergy at the time of the evaluations were excluded. Incomplete medical records were also excluded.

The epidemiological, medical, and therapeutic information of each patient who consulted in our center were all recorded, electronically bachelor in our organisation, and were hands extracted for the purpose of the study using the following keywords: "atypical", "unusual", "uncommon", "nasal", "respiratory", "bronchial", "ear", and "centre".

2.two. 24 h HEMII-pH

The HEMII-pH catheter was composed of 8 impedance ring pairs and two pH electrodes (Versaflex Z®, LPR ZNID22+8R FGS 9000-17; Digitrapper pH-Z testing System, Medtronic, Hauts-de-French republic, Lille, France, Supplementary file). The catheter model used was introduced transnasally and chosen based on the esophageal length of the patient. Six impedance segments were placed along the esophagus zones (Z1 to Z6) below the upper esophagus sphincter (UES). Two additional impedance segments were placed 1 and ii cm above the UES in the hypopharyngeal crenel. The configuration of this catheter enabled the recording of changes in intraluminal impedance at each point. The two pH electrodes were placed five cm above the LES and one–two cm above the UES. The HEMII-pH probe was placed in the morning earlier breakfast (8:00 A.M). A hypopharyngeal reflux consequence (HRE) was divers every bit an episode that reached two hypopharyngeal impedance sensors. A LPR diagnosis was given if there was ≥1 acrid or nonacid HRE [13]. Acrid reflux was defined as an episode with pH ≤ 4.0. Nonacid reflux consisted of an episode with pH > 4.0. The HEMII-pH tracing was electronically analyzed by the software and the result was verified past two senior physicians. LPR was divers as acid when the ratio of the number of hypopharyngeal acid reflux episodes/number of nonacid reflux episodes was >2. LPR was defined equally nonacid when the ratio of the number of acid reflux episodes/number of nonacid reflux episodes <0.v. Mixed reflux consisted of a ratio ranging from 0.51 to 2.0. GERD was divers as a DeMeester score >xiv.72 or a length of time >4.0% of the 24 h recording spent beneath pH 4.0.

2.3. Finding Development, Treatment, and Direction of Atypical Clinical Presentations

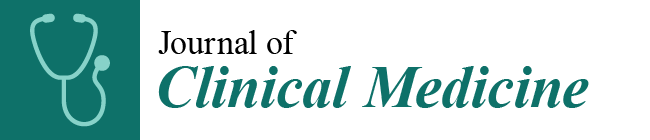

The management of patients in our reflux clinics is summarized in Figure ane. In do, afterwards the HEMII-pH diagnosis, the laryngologists started a certain treatment depending on the HEMII-pH features. The treatment scheme included a nutrition, behavioral changes, and the employ of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), alginate, or magaldrate for iii months. PPIs were taken once or twice daily before meals depending on the blueprint of reflux events (daytime, nighttime reflux events). Alginates were taken twice or three times daily afterwards the chief meals in the case of weakly acid (mixed) or nonacid LPR. Diet recommendations were based on a validated European diet scheme [xiv]. The treatment of patients was custom-tailored at 3 and 6 months regarding the development of RSS.

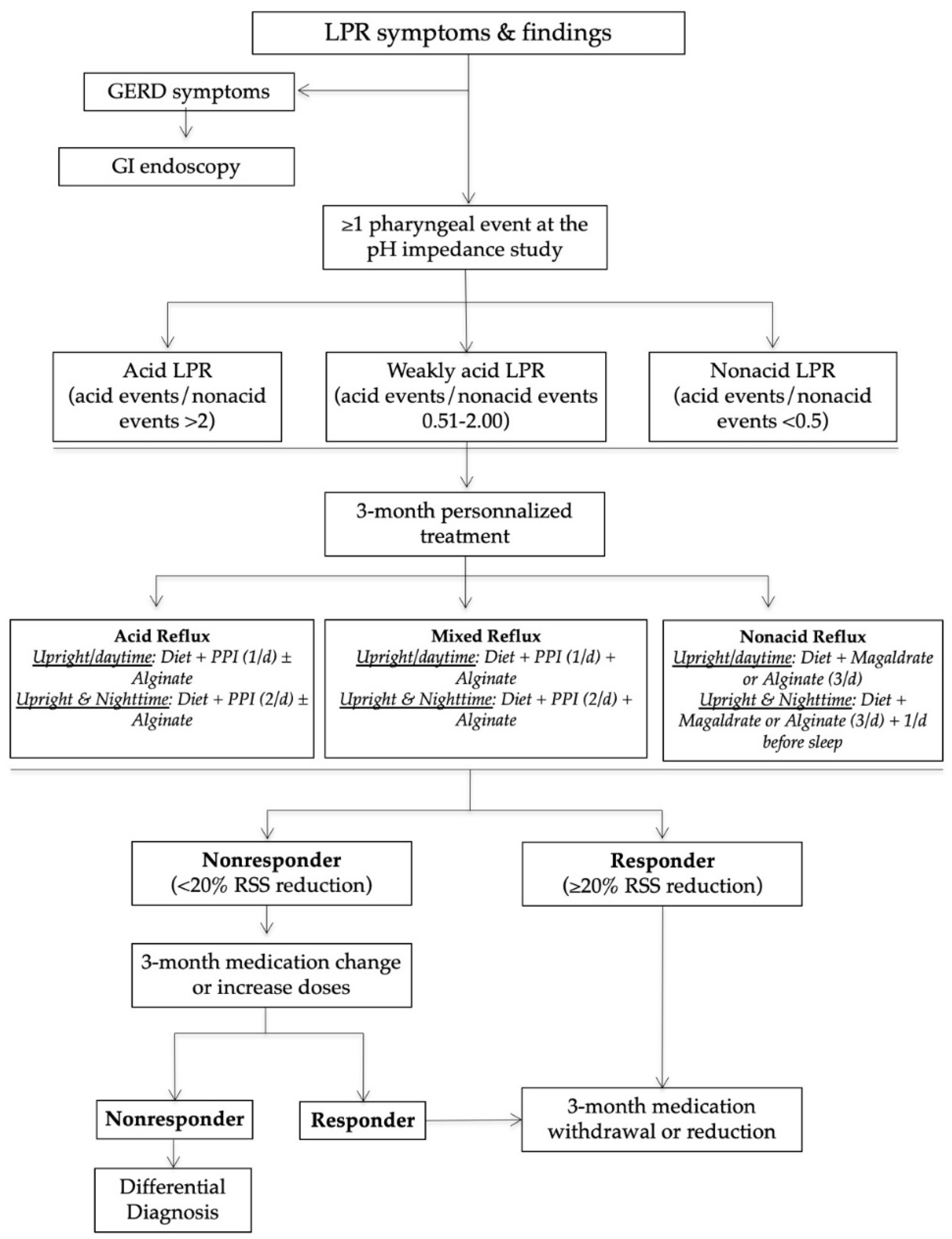

Nonresponders or those presenting with an unusual clinical presentation benefited from additional general and specific (related to the anatomical findings) examinations in order to identify a differential diagnosis or comorbidities associated with LPR (Figure two).

three. Results

From the 351 patients who had a positive HEMII-pH diagnosis, 24 patients met our inclusion criteria. Iii patients were excluded because in that location were no posttreatment information in the medical record. The atypical findings consisted of recurrent aphthosis or burning mouth (Due north = ix), recurrent burps and abdominal disorders (N = 2), posterior nasal obstruction (N = 2), recurrent astute suppurative media otitis (N = 2), severe vocal fold dysplasia (N = 2), recurrent acute rhinopharyngitis (Northward = one), chronic tearing (N = one), recurrent aspirations (N = 1), and tracheobronchitis (N = ane). The patient features are reported in Tabular array 1, Tabular array two and Table iii.

iii.1. Oral Atypical Manifestations

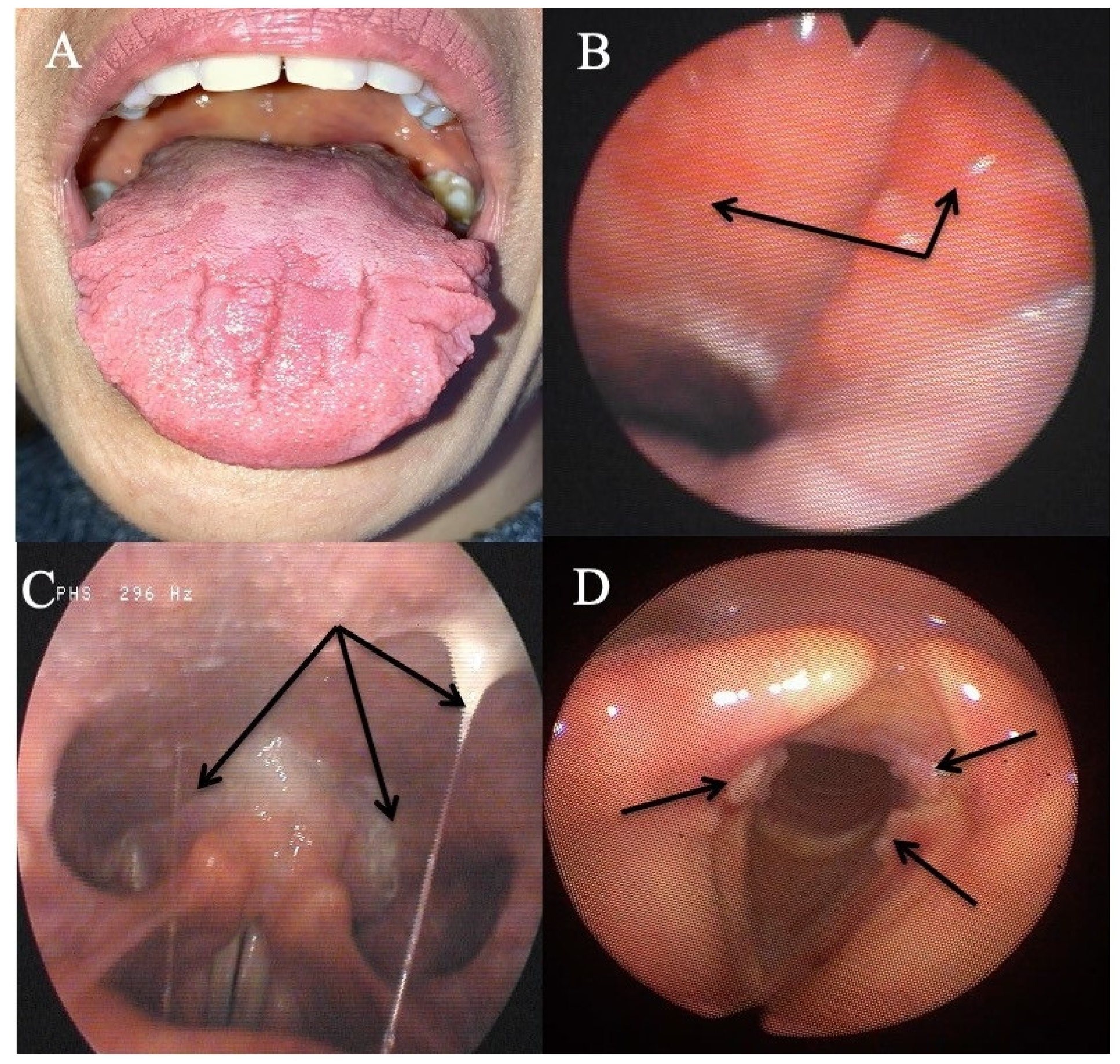

Eleven patients reported oral atypical manifestations. From them, two patients had recurrent aphthosis and burning oral cavity syndrome, while 7 individuals had severe isolated burning natural language/mouth. Before submitting them to HEMII-pH, the patients benefited from complete dental and maxillofacial examinations, excluding the post-obit lesions or conditions associated with secondary called-for mouth syndrome: atrophic glossitis, geographical tongue, other aphthosis causes, dysplasia, lichen, mycosis, Sjogren, autoimmune illness, vitamin disorders, or hypersensitivity to dental materials. After the exclusion of these causative factors, they benefited from a reflux consultation and a 24 h HEMII-pH. As exhibited in Table 1, LPR was identified in all patients, consisting of acid (N = 7), weakly acrid (N = 1), and element of group i (North = one) LPR. Regarding the HEMII-pH features, patients received a personalized treatment and the disorders/lesions regressed later on a 3- to 6-month therapy. There was no recurrence of the disorder at the last f time, ranging from 6 months to 3 years. Annotation that patient number 6 as well developed fissured tongue (Figure 3A), which did not change after treatment.

Patient number 3 was living abroad and was referred to our clinic with severe anorexia related to burning rima oris syndrome resistant to three- to vi-month anti-reflux therapy (i.eastward., the use of PPIs, alginate, and an antireflux diet). The patient lost fifteen kg over the previous six months. The HEMII-pH revealed alkaline LPR, and the patient was treated with magaldrate (four times daily) for 6 months. As the symptoms did not improve, an additional check-up was proposed to the patient and a histamine intolerance was detected. The symptoms and findings disappeared later on 2 months of a histamine-free diet.

Among the patients with oral findings, 2 patients complained of recurrent burps, halitosis, and abdominal hurting. As they were resistant to PPI therapy, patients were referred to our specialized clinic. LPR diagnosis was confirmed with the HEMII-pH, and the digestive work-up (biology and lactose hydrogen breath test) revealed gluten (patient n10) and lactose (patient n11) intolerance. The gluten-free and lactose-free diets were sufficient to significantly improve laryngopharyngeal and digestive symptoms in these patients over the long-term follow-up (four years).

3.2. Otological and Nasal Atypical Manifestations

6 patients had otological or nasal singular LPR presentations (Table 2). Amidst them, three individuals reported resistant chronic nasal obstacle, which was not related to a nasal or nasopharyngeal tumor, polyposis, chronic rhinosinusitis, septal divergence, allergic rhinitis, inflammatory nasal disease, cartilage hypotonia, infection, or chemic- or drug-induced rhinitis. A CT browse of the nose and sinuses was unremarkable. In that location was no history of nasal surgery and they did non respond to a 3-month topical treatment including saline solution irrigation and two dissimilar corticosteroids (mometasone furoate and budesonide). The patients benefited from acoustic rhinomanometry to confirm the nasal obstruction, which was related to inferior turbinate hypertrophy. In patient number 13, a turbinate edema was located in the back of the turbinate. The RSS and the nasal obstruction of patients significantly improved later on a 3- to 6-month antireflux therapy. Two patients were weaned from the antireflux medication and were clinically controlled with the antireflux diet over the long-term. 1 patient was non weaned from the alginate-based treatment, because she continued to take laryngopharyngeal symptoms (LPR chronic course). At baseline, this patient likewise had chronic tearing related to an inferior meatus edema. Although the laryngopharyngeal symptoms persisted, the inferior meatus edema and the related fierce disorder disappeared.

3 patients had an otological clinical presentation associated with LPR (Tabular array ii). Patient number fifteen had recurrent acute suppurative otitis media (3 to 4 times annually) throughout the last decade. During the last episode, the otolaryngologists observed jutting and erythema of both tympanic membranes and the patient benefited from antibody/anti-inflammatory treatment. The predisposing factors for recurrent otitis media were all excluded (due east.g., immunological disorders, nasal disorder, rhinitis, and chemic exposure). Patient number sixteen also reported otological disorder (retraction pocket) without history or favoring factors. These ii patients were addressed to the reflux clinics past general otolaryngologists who observed LPR-related signs and erythema of the nasopharyngeal cavity (Figure 3B). Acrid gaseous upright and daytime LPR was confirmed in both cases. The personalized treatments led to a consummate resolution of the recurrent acute otitis media history and retraction pocket later on treatment. There was no recurrence at one twelvemonth posttreatment. The last patient had a chronic class of rhinopharyngitis with astringent rhinorrhea, postnasal baste, nasal obstruction, and face and ear pressure. Nasal fiberoptic endoscopy revealed pregnant nasopharyngeal viscid fungus and erythema (Figure 3C). The CT scan and otological examinations (i.e., otoscopy, tympanometry, and audiometry) were unremarkable. At that place was also a dust allergy that was controlled by antihistamines. As for the other patients, the HEMII-pH confirmed the diagnosis, and the rhinopharyngitis-related symptoms disappeared after a personalized handling.

The third patient group included 2 individuals with severe vocal fold dysplasia, one with recurrent aspirations and related lung infections, and some other with recurrent tracheobronchitis. No patient smoked or had tobacco or chemical exposure history. Prior to the reflux consultation, patients with vocal fold leukoplakia underwent a direct laryngobronchoscopy with a biopsy confirming severe dysplasia (Figure 3D). Patients with aspiration and tracheobronchitis benefited from a complete pulmonary work-upwardly, including lung spirometry, bronchoscopy, and chest CT-scan, which were normal. The patient with aspiration had no neurological disorder, and videofluoroscopy and bronchoscopy were unremarkable. HEMII-pH identified acid or weakly acid LPR in these patients. The patient disorders disappeared with the personalized treatment and there was no recurrence over the follow-up menses.

4. Discussion

Laryngopharyngeal reflux is occasionally associated with nonspecific symptoms and findings, which brand diagnosis challenging for unaware physicians [15]. The involvement of LPR in the development of several inflammatory weather condition of the upper aerodigestive tract has increasingly been studied over the by decades, reporting potential involvement in rhinological, otological, and laryngological diseases [5,6,seven,8]. In this study, our team shared some clinical observations where the diagnosis and the treatment of LPR disease had a significant impact on the resolution of specific weather condition that are currently not or poorly known to be associated with reflux.

The interest of LPR in the development of oral disorders was suspected for a long time, the start reports dating from the 1970s [16]. In the present study, we reported several patients with main called-for mouth syndrome that was not attributed to any dental or general status. Interestingly, nosotros observed that symptoms significantly improved or resolved with an adequate handling and a long-term antireflux diet. A few studies investigated the involvement of reflux in dental lesions [17], or primary burning mouth syndrome [18,19,20], but authors reported conflicting results, which may be related to methodological discrepancies across studies [21]. Indeed, the majority of authors studied the association between burning mouth syndrome and reflux considering GERD and non LPR diagnostic criteria [18,xix,20]. To date, information technology has been demonstrated that patients with LPR may not have GERD and vice versa [1]. The development of burning or pain mouth may exist related to mucosal injury related to pepsin, which may exist hands detected in saliva samples with peptest. Thus, the saliva pepsin detection could be useful to investigate the potential interest of LPR in principal burning mouth syndrome, "idiopathic" aphthosis, or fissured natural language.

Several studies demonstrated that reflux events may reach nasopharyngeal and nasal regions [22,23]. In this study, we identified patients who had nasal or otological findings associated with LPR, i.east., nasal obstruction, excessive nasopharyngeal mucus, or recurrent acute media otitis. The pharyngeal reflux events are known to be mainly gaseous, occurring upright and in daytime [24]. The occurrence of rhinopharyngeal reflux episodes may easily support the development of a reflux-related nasopharyngeal inflammation and the local production of viscid nasopharyngeal mucus, the obstacle of the Eustachian tube, and the development of otitis media disorders. Furthermore, pepsin has been identified in the secretion of otitis media in several studies [6,25,26]. According to nasal obstacle, two contempo studies supported that LPR may lead to edema of the nasal mucosa, including the posterior part of the inferior turbinate, every bit observed in this study [27,28]. Interestingly, Magliulo et al. institute pepsin in the tears [29], which may back up the occurrence of a relationship between laryngopharyngeal reflux and tear disorders through the injury of the nasal mucosa of the inferior meatus.

The pepsin-related mucosal injury was initially studied in vocal fold tissues [three,xxx]. Pepsin may induce macroscopic and microscopic changes in the song fold mucosa, including epithelial prison cell dehiscence, microtraumas, inflammatory infiltrates, Reinke space dryness, mucosal drying, and epithelial thickening [31]. The development of severe dysplasia and its resolution after LPR treatment may probably back up the potential bear upon of LPR in the development of some vocal fold morphological changes in nonsmoker patients. Clinically, LPR may accept an bear on on the clinical presentation and the therapeutic response of patients with asthma [8], which supports that the LPR-related inflammation may attain the bronchi. The observation of patients with LPR and chronic bronchitis that was not attributed to another disease supports the importance to go on in mind that LPR may be an irritative gene of the lower airway. In the same manner, pepsin was found in the trachea and bronchi of patients with idiopathic stenosis [32].

In this instance series, the association betwixt LPR and atypical findings is possible but not proven. Despite the occurrence of an singular and, therefore, different clinical presentation of LPR, the use of the term "LPR" has to exist kept regarding the potential similar physiological mechanisms than classical LPR. According to our HEMII-pH analyses and previous studies [24], in both atypical and mutual clinical presentations of LPR, pharyngeal reflux events were gaseous and occurred in daytime and upright in the majority of patients. The detection of pepsin and other gastroduodenal enzymes in saliva, nasal, or bronchial secretions may course the basis for a future study and possibly demonstrate the impact of LPR in the development of many unusual conditions. Gastroduodenal enzymes may irritate the upper aerodigestive tract mucosa but they may have an boosted role on the local microbiota [33]. In the digestive area, much research has demonstrated the importance of gut leaner in mucosa homeostasis, protection, recovery, or renewal [34,35]. Similarly, the disquisitional role of microbiota was reported in respiratory tract diseases, such as tracheal stenosis or asthma [36,37]. Thus, it seems conceivable that LPR may touch the upper aerodigestive tract microbiota, leading to the evolution of some disorders.

The primary limitation of the present clinical study is the lack of tissue-related demonstrations of the involvement of reflux in the evolution of the atypical disorders. However, the occurrence of LPR at the HEMII-pH report and the complete resolution after handling strongly support a clinical association. The retrospective design, the depression number of included patients, and the short follow-up time of some patients are additional limitations of the study.

v. Conclusions

LPR may present with various clinical presentations, including oral fissure, eye, tracheobronchial, nasal, or laryngeal findings, which may all backslide with an adequate handling. Future studies are needed to amend specify the relationship between LPR and these singular findings through analyses identifying gastroduodenal enzymes in the enflamed tissue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.50., S.H., P.D.K. and Southward.S.; Methodology/Organization, F.B. and C.C.-H.; Writing—Original Draft Training, J.R.L. and P.D.Chiliad.; Writing—Review and Editing, P.D.K., S.South. and S.H.; Supervision, S.Due south., S.H. and P.D.K. All authors take read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This enquiry received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The IRB of CHU Saint-Pierre approved the study (Brussels, northward°BE076201837630).

Informed Consent Statement

Patients had to consent to participate to the report.

Data Availability Argument

Data may exist available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of involvement.

References

- Lechien, J.R.; Akst, L.G.; Hamdan, A.L.; Schindler, A.; Karkos, P.D.; Barillari, M.R.; Calvo-Henriquez, C.; Crevier-Buchman, L.; Finck, C.; Eun, Y.Thousand.; et al. Evaluation and Management of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease: State of the Art Review. Otolaryngol. Caput Neck Surg. 2019, 160, 762–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimara, M.J.; Randall, D.R.; Allen, J.; Figueredo, E.; Johnston, N. Proximal reflux: Biochemical mediators, markers, therapeutic targets, and clinical correlations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1481, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, T.L.; Johnston, N. Pepsin equally a marker of extraesophageal reflux. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2010, 119, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Ren, X.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Westward.; He, Z. PepsinA every bit a Marker of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Detected in Chronic Rhinosinusitis Patients. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 156, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.; Lim, H.J.; Gill, Thou.; Smith, T.L.; Merati, A.; Toohill, R.J.; Loehrl, T.A. Treatment of postnasal drip with proton pump inhibitors: A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am. J. Rhinol. 2007, 21, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Hans, Southward.; Simon, F.; Horoi, M.; Calvo-Henriquez, C.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.M.; Mayo-Yáñez, M.; Bartel, R.; Piersiala, K.; Nguyen, Y.; et al. Association between Laryngopharyngeal Reflux and Media Otitis: A Systematic Review. Otol. Neurotol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Akst, L.M.; Saussez, South.; Crevier-Buchman, L.; Hans, S.; Barillari, Chiliad.R.; Calvo-Henriquez, C.; Bock, J.M.; Carroll, T.50. Involvement of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux in Select Nonfunctional Laryngeal Diseases: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 194599820933209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, J.P.; Parikh, S.; Orlando, R.C.; Johnston, Due north.; Allen, J.; Tinling, Due south.P.; Belafsky, P.; Arevalo, Fifty.F.; Sharma, N.; Castell, D.O.; et al. Review article: Reflux and its consequences—The laryngeal, pulmonary and oesophageal manifestations. In Proceedings of the ninth International Symposium on Human Pepsin (ISHP), Kingston-upon-Hull, UK, 21–23 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lechien, J.R.; Bobin, F.; Muls, V.; Saussez, Southward.; Remacle, 1000.; Hans, S. Reflux clinic: Proof-of-concept of a Multidisciplinary European Dispensary. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Bobin, F.; Muls, V.; Mouawad, F.; Dequanter, D.; Horoi, M.; Thill, M.P.; Rodriguez Ruiz, A.; Saussez, Due south. The efficacy of a personalised treatment depending on the characteristics of reflux at multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH monitoring in patients with acrid, not-acid and mixed laryngopharyngeal reflux. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2021, 46, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Rodriguez Ruiz, A.; Dequanter, D.; Bobin, F.; Mouawad, F.; Muls, V.; Huet, K.; Harmegnies, B.; Remacle, Due south.; Finck, C.; et al. Validity and Reliability of the Reflux Sign Assessment. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2020, 129, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Saussez, S.; Schindler, A.; Karkos, P.D.; Hamdan, A.L.; Harmegnies, B.; De Marrez, 50.M.; Finck, C.; Journe, F.; Paesmans, M.; et al. Clinical outcomes of laryngopharyngeal reflux treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 1174–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppo, T.; Sanz, A.F.; Nason, K.S.; Carroll, T.50.; Rosen, C.; Normolle, D.P.; Shaheen, N.J.; Luketich, J.D.; Jobe, B.A. How much pharyngeal exposure is "normal"? Normative data for laryngopharyngeal reflux events using hypopharyngeal multichannel intraluminal impedance (HMII). J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2012, xvi, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Bobin, F.; Muls, V.; Horoi, 1000.; Thill, K.P.; Dequanter, D.; Rodriguez, A.; Saussez, Southward. Patients with acid, high-fat and low-protein diet have higher laryngopharyngeal reflux episodes at the impedance-pH monitoring. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 277, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Allen, J.E.; Barillari, M.R.; Karkos, P.D.; Jia, H.; Ceccon, F.P.; Imamura, R.; Metwaly, O.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.M.; Bock, J.1000.; et al. Management of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Around the Globe: An International Written report. Laryngoscope 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, G.F. Erosion every bit the presenting symptom in hiatus hernia. A case report. Br. Dent. J. 1971, 131, 455–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.M.; Calvo Henriquez, C.; Mouawad, F.; Ristagno, C.; Barillari, M.R.; Schindler, A.; Nacci, A.; Bouland, C.; Laino, L.; et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux, gastroesophageal reflux and dental disorders: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preetha, A.; Sujatha, D.; Patil, B.A.; Hegde, Southward. Oral manifestations in gastroesophageal reflux illness. Gen. Paring. 2015, 63, e27–e31. [Google Scholar]

- Hakeem, A.; Fitzpatrick, South.G.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Islam, M.North.; Cohen, D.M. Clinical characterization and handling outcome of patients with burning mouth syndrome. Gen. Dent. 2018, 66, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, D.; Trudgill, Northward. Managing a patient with burning mouth syndrome. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2015, vi, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Hans, S.; De Marrez, L.Thou.; Dequanter, D.; Rodriguez, A.; Muls, V.; Ben Abdelouahed, F.; Evrard, 50.; Maniaci, A.; Saussez, Due south.; et al. Prevalence and Features of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux in Patients with Primary Burning Mouth Syndrome. Laryngoscope 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunworth, J.D.; Mahboubi, H.; Garg, R.; Johnson, B.; Brandon, B.; Djalilian, H.R. Nasopharyngeal acid reflux and Eustachian tube dysfunction in adults. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2014, 123, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunworth, J.D.; Garg, R.; Mahboubi, H.; Johnson, B.; Djalilian, H.R. Detecting nasopharyngeal reflux: A novel pH probe technique. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2012, 121, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Bobin, F.; Dapri, M.; Eisendrath, P.; Salem, C.; Mouawad, F.; Horoi, Chiliad.; Thill, M.P.; Dequanter, D.; Rodriguez, A.; et al. Hypopharyngeal-Esophageal Impedance-pH Monitoring Profiles of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Patients. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Yu, Z.; Yu, R.; Yang, H.; Zou, J.; Ren, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, D. Correlation of pathogenic effects of laryngopharyngeal reflux and bacterial infection in Come up of children. Acta Otolaryngol. 2021, one–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, R.C.; Soundar, S.; Tonb, D.; Bolling, L.; Yoo, E.; Nadal, T.; Grindle, C.; Field, E.; He, Z. The role of gastric pepsin in the inflammatory cascade of pediatric otitis media. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Cervix Surg. 2015, 141, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamizan, A.W.; Choo, Y.Y.; Loh, P.V.; Abd Talib, North.F.; Mohd Ramli, Chiliad.F.; Zahedi, F.D.; Husain, South. The association between the reflux symptoms index and nasal symptoms among patients with non-allergic rhinitis. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2021, 135, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceylan, S.M.; Kanmaz, M.A.; Disikirik, I.; Karadeniz, P.G. Peak nasal inspiratory airflow measurements for assessing laryngopharyngeal reflux treatment. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliulo, 1000.; Footstep, A.; Plateroti, R.; Plateroti, A.G.; Cascella, R.; Solito, C.; Rossetti, V.; Iannella, Thou. Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease in adult patients: Tears and pepsin. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, T.L.; Johnston, N. Pepsin in gastroesophageal and extraesophageal reflux: Molecular pathophysiology and diagnostic utility. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Cervix Surg. 2020, 28, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Saussez, Due south.; Harmegnies, B.; Finck, C.; Burns, J.A. Laryngopharyngeal Reflux and Voice Disorders: A Multifactorial Model of Etiology and Pathophysiology. J. Vocalism 2017, 31, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumin, J.H.; Johnston, North. Evidence of extraesophageal reflux in idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; De Vos, Northward.; Everard, A.; Saussez, Due south. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: The microbiota theory. Med. Hypotheses 2021, 146, 110460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagi, Due east.; Candela, M.; Turroni, Due south.; Garagnani, P.; Franceschi, C.; Brigidi, P. Ageing and gut microbes: Perspectives for health maintenance and longevity. Pharmacol. Res. 2013, 69, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, J.P.; Wallace, J.L.; Buret, A.1000.; Deraison, C.; Vergnolle, N. Gastrointestinal biofilms in wellness and illness. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillel, A.T.; Tang, S.Due south.; Carlos, C.; Skarlupka, J.H.; Gowda, M.; Yin, 50.X.; Motz, Thousand.; Currie, C.R.; Suen, G.; Thibeault, South.L. Laryngotracheal Microbiota in Adult Laryngotracheal Stenosis. mSphere 2019, iv, e00211–e00219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.H.F.; Teo, S.M.; Sly, P.D.; Holt, P.G.; Inouye, M. The intersect of genetics, surroundings, and microbiota in asthma-perspectives and challenges. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure one. Management algorithm of LPR patients. Abbreviations: GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; GI = gastrointestinal; LPR = laryngopharyngeal reflux; PPI = proton pump inhibitor; RSS = reflux symptom score.

Figure one. Direction algorithm of LPR patients. Abbreviations: GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; GI = gastrointestinal; LPR = laryngopharyngeal reflux; PPI = proton pump inhibitor; RSS = reflux symptom score.

Effigy 2. Nonresponder direction. Abbreviations: GI = gastrointestinal; LES = lower esophageal sphincter; LPR = laryngopharyngeal reflux; UES = upper esophageal sphincter. * = differential diagnosis is a condition that may exist associated with similar symptoms and findings. ** = Some symptoms may appear after the intake of medication (adverse events of drugs).

Effigy ii. Nonresponder management. Abbreviations: GI = gastrointestinal; LES = lower esophageal sphincter; LPR = laryngopharyngeal reflux; UES = upper esophageal sphincter. * = differential diagnosis is a condition that may be associated with similar symptoms and findings. ** = Some symptoms may appear after the intake of medication (adverse events of drugs).

Figure 3. Some atypical findings associated with reflux. Fissured natural language (A), erythema of the nasopharynx and Eustachian meatus (B), gummy mucus from nasopharynx to oropharynx (C), and leukoplakia (D).

Figure 3. Some atypical findings associated with reflux. Fissured tongue (A), erythema of the nasopharynx and Eustachian meatus (B), sticky mucus from nasopharynx to oropharynx (C), and leukoplakia (D).

Table 1. Data of patients with oral manifestations.

Table 1. Data of patients with oral manifestations.

| PN | Chiliad | Age | Baseline Features | Post-Treatment Features | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atypical Presentation | HEMII-pH/RSS | Treatment | RSS/RSA | Presentation Evolution | Long-Term Follow-Upwardly | |||

| 1 | M | 36 | Recurrent aphthosis and burning mouth | Upright acid reflux (58) * | Strict nutrition | RSS: thirteen | Resolution of aphthosis and | Long-term diet |

| Dental bank check-upwards: normal | GI: normal | PPIs | RSA: 10 | burning mouth | No recurrence (3-y) | |||

| RSS: 48–RSA: 26 | Magaldrate | |||||||

| 2 | F | 55 | Recurrent aphthosis and burning mouth | Upright acid reflux (22) * | Strict diet | RSS: 5 | Resolution of aphthosis and | Long-term diet |

| Dental check-up: normal | GI: not performed | PPIs | RSA: NP | called-for mouth | No recurrence (6-m) | |||

| RSS: 50–RSA: 26 | Alginate | |||||||

| iii | G | 31 | Mouth burning and severe anorexia | Upright nonacid reflux (11) | Histamine-free | RSS: 64 | Resolution of pain and | Long-term histamine-complimentary |

| GI/dental cheque-upwardly: normal | GI: normal | Diet | RSA: NP | weight gain | diet. | |||

| Nutritionist: Histamine intolerance | RSS: 148–RSA: 14 | No recurrence (1-y) | ||||||

| iv | G | 38 | Natural language burning | Upright weakly acid reflux (15) | Strict diet | RSS: 16 | Resolution of tongue | Long-term diet |

| Dental cheque-upwards: normal | GI: normal | PPIs | RSA: 23 | burning | No recurrence (1-y) | |||

| RSS: 131–RSA: 37 | Alginate | |||||||

| 5 | Thou | 55 | Tongue burning | Upright acid reflux (27) | Strict nutrition | RSS: 48 | Reduction of tongue | Long-term diet |

| Dental cheque-up: normal | GI: GERD, hiatal hernia | PPIs | RSA: 21 | burning | Long-term PPIs and | |||

| RSS: 76–RSA: 24 | Magaldrate | Magaldrate (1-y) | ||||||

| 6 | F | 53 | Tongue burning and fissured tongue | Upright acid reflux (nineteen) | Strict diet | RSS: 135 | Reduction of tongue | Long-term nutrition |

| Dental check-upwardly: normal | GI: GERD, esophagitis | PPIs | RSA: 22 | Burning only no change | Long-term intermittent | |||

| RSS: 247–RSA: 28 | Magaldrate | in fissured tongue | Magaldrate (9-m) | |||||

| 7 | F | 54 | Natural language and mouth burning | Upright acid reflux (38) * | Strict diet | RSS: 19 | Resolution of natural language | Long-term nutrition |

| Dental check-up: normal | GI: GERD | PPIs | RSA: 13 | burning | No recurrence (three-y) | |||

| RSS: 88–RSA: 26 | Magaldrate | |||||||

| 8 | F | 62 | Natural language and mouth burning | Upright acid reflux | Strict diet | RSS: 19 | Resolution of natural language | Long-term nutrition |

| Dental check-up: normal | GI: GERD, esophagitis | PPIs | RSA: 32 | called-for | One recurrence controlled | |||

| RSS: 203–RSA: 22 | Alginate | with alginate (three-y) | ||||||

| 9 | F | 64 | Tongue and mouth burning | Upright acid reflux (7) | Strict alkaline | RSS: 12 | Resolution of tongue | Long-term nutrition |

| Dental check-up: normal | GI: normal | Diet | RSA: NP | called-for | No recurrence (half dozen-m) | |||

| RSS: 124–RSA: 32 | ||||||||

| 10 | F | 31 | Recurrent burps and intestinal pain | Upright acid reflux (eighteen) | Gluten-costless | RSS: 40 | Resolution of burps and | Long-term gluten-free |

| GI check-up: gluten intolerance | GI: bulbitis | Diet | RSA: 17 | Abdominal pain | diet. | |||

| RSS: 167–RSA: 20 | No recurrence (four-y) | |||||||

| 11 | F | 36 | Recurrent burps and abdominal pain | Upright nonacid reflux (ii) | Lactose-gratuitous | RSS: xvi | Resolution of burps and | Long-term lactosis-free |

| GI cheque-up: lactose intolerance | GI: normal | Diet | RSA: 21 | Abdominal pain | diet. | |||

| RSS: 111–RSA: 31 | No recurrence (four-y) | |||||||

Table 2. Data of patients with oral manifestations.

Table 2. Information of patients with oral manifestations.

| PN | G | Age | Baseline Features | Mail-Treatment Features | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atypical Presentation | HEMII-pH/RSS | Treatment | RSS/RSA | Presentation Evolution | Long-Term Follow-Up | |||

| 12 | F | 64 | Resistant chronic nasal obstruction # | Upright weakly acid reflux (12) | Strict diet | RSS: 67 | Resolution of nasal | Long-term diet |

| Nasosinusal check-up: hypertrophy of | GI: normal | PPIs | RSA: NP | obstruction | No recurrence (6 months) | |||

| the posterior part of the junior turbine | RSS: 250–RSA: 29 | Alginate | ||||||

| 13 | F | l | Resistant chronic nasal obstruction # | Upright acid reflux (24) | Strict diet | RSS: 43 | Resolution of nasal | Long-term diet |

| Nasosinusal check-upwards: hypertrophy of | GI: not performed | PPIs | RSA: NP | obstruction | No recurrence (6 months) | |||

| the posterior office of the inferior turbine | RSS: 58–RSA: 12 | Alginate | Septoplasty not required | |||||

| 14 | F | 66 | Resistant chronic nasal obstruction | Upright weakly acrid reflux (9) * | Strict alkaline | RSS: 184 | Resolution of nasal | Long-term diet and alginate |

| and tearing | GI: not performed | Diet | RSA: NP | obstruction and tearing | No recurrence (six-m) of | |||

| Nasosinusal cheque-upwardly: hypertrophy of | RSS: 210–RSA: 32 | Resolution of edema of | tear and nasal symptoms | |||||

| the posterior role of the inferior turbine | inferior and middle meatus | Chronic pharynx symptoms | ||||||

| fifteen | F | 35 | Recurrent suppurative media otitis and | Upright acid reflux (four) * | Strict alkaline | RSS: 2 | Resolution of media | Long-term diet |

| Ear force per unit area and pain | GI: non performed | Diet | RSA: 7 | otitis | No recurrence (1-y) of | |||

| Nasosinusal check-up: normal | RSS: 11–RSA: twenty | symptoms or tympanic | ||||||

| Otological bank check-upwards: retraction pocket | membrane findings. | |||||||

| 16 | M | 37 | Chronic media otitis | Upright acid reflux (iii) | Strict alkaline | RSS: 48 | Improvement of nasal | Long-term diet and curt |

| Nasosinusal check-upwards: obstruction and | GI: not performed | Diet | RSA: NP | obstacle | period of alginate | |||

| erythema of the Eustachian tube. ** | RSS: 73–RSA: 36 | No recurrence (1-y) | ||||||

| 17 | Thou | 36 | Recurrent rhinopharyngitis/otitis | Upright weakly acid reflux (11) | Strict diet | RSS: 52 | Resolution of rhino- | Long-term diet |

| Otological cheque-up: normal | GI: non performed | PPIs | RSA: 20 | pharyngitis posttreatment | No recurrence (half dozen months) | |||

| Nasal check-upwardly: controlled dust allergy | RSS: 107–RSA: 29 | Alginate | ||||||

Table 3. Broncho-laryngeal manifestations of reflux.

Table 3. Broncho-laryngeal manifestations of reflux.

| PN | G | Age | Baseline Features | Post-Treatment Features | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atypical Presentation | HEMII-pH/RSS | Treatment | RSS/RSA | Presentation Development | Long-Term Follow-Up | |||

| 18 | F | 34 | Astringent idiopathic song fold dysplasia | Upright acid reflux (11) | Strict alkaline | RSS: 9 | Resolution of dysplasia | Long-term diet |

| Laryngeal check-up: normal | GI: not performed | Alginate | RSA: 20 | within 6 months | No recurrence (half-dozen months) | |||

| No tobacco/toxic exposition history | RSS: 34–RSA: 39 | Diet | ||||||

| nineteen | K | 45 | Severe idiopathic song fold dysplasia | Upright acid reflux (22) | Strict alkaline | RSS: 16 | Resolution of dysplasia | Long-term nutrition |

| Laryngeal check-upwardly: normal | GI: not performed | Diet | RSA: 18 | inside six months | No recurrence (nine months) | |||

| No tobacco/toxic exposition history | RSS: 73–RSA: 23 | |||||||

| 20 | M | 38 | Daily aspirations and pneumonia | Upright acid reflux (39) * | Strict alkaline | RSS: 81 | Resolution of dysplasia | Long-term nutrition |

| Lung/swallowing check-up: normal | GI: esophagitis | Nutrition | RSA: 18 | within vi months | No recurrence (half dozen months) | |||

| RSS: 156–RSA: 27 | Alginate | |||||||

| 21 | F | 65 | Recurrent tracheobronchitis | Upright weakly acid reflux (34) * | Strict diet | RSS: 110 | Resolution of tracheo- | Long-term diet |

| Lung bank check-upward: normal | GI: LES insufficiency | Magaldrate | RSA: nineteen | bronchitis within half-dozen months | Magaldrate (sometimes) | |||

| No tobacco/asthma history | RSS: 415–RSA: 24 | No recurrence (6 months) | ||||||

| Publisher'southward Annotation: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/10/11/2439/htm

,

,

0 Response to "Evaluation and Management of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease State of the Art Review"

Post a Comment